The National Gallery of Art has put on an extraordinary exhibit of a great Renaissance artist who is almost unknown outside his native land: Alonso Berruguete (ca. 1486-1561) was the first and greatest sculptor of the Spanish Renaissance.

He is little-known outside of his native country, however, because much of his artwork is embedded in the massive gilded wooden retablos that he built as towering backdrops for the main altars in cathedrals and monastery churches in and around his native Valladolid in central Spain. The retablos, multi-leveled and crammed with multiple images, carved and painted, of Christ and the saints, some of enormous size so they could be seen by worshipers far below, cannot be transported. And the cities of Valladolid and Toledo, where Berruguete did most of his work, are slightly off the tourist trail, so few Americans are familiar with his sculpture.

For me and for many, that just changed as a result of this exhibition:

Fortunately for American lovers of art and especially sacred art, during one of its periodic anticlerical phases during the 1830s, the Spanish government xpropriated and forcibly secularized the site of one of Berruguete’s most impressive altarpieces: the Benedictine monastery church of San Benito el Real in Valladolid.

Berruguete’s 40-foot-high retablo was mostly destroyed in this burst of iconoclasm and many of its sculptures ended up in a municipal museum. That made it possible for them to travel outside of Spain, and their portability has enabled the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., to assemble the first major U.S. exhibition of Berruguete’s work.

The exhibition includes some of his most impressive sculptures from San Benito and nearby churches, together with paintings, drawings, and pieces by other Spanish artists who were contemporaries of his that give his output an artistic context. The exhibition, scheduled to run through February 17, is a small one: just 40 artworks in two rooms. It is complicated by the fact that Berruguete, like many successful artists of his time (and Andy Warhol in our own day), employed a workshop of apprentices to help fill his numerous commissions, so it is difficult to ascertain how much of any particular sculpture is actually the work of his own hand.

Yet all of them—figures of the crucified Christ and his mother, saints, and Old Testament prophets–bear the mark of Berruguete’s unquestioned ability to meld wood, gilding, classical technique learned from Italian Renaissance masters, and a flair for emotional expressiveness into sculptures of astonishing religious intensity.

Valladolid, about 120 miles north of Madrid, was the capital of the kingdom of Castille during Berruguete’s lifetime and thus, effectively, the capital of Spain itself. Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castille were married in Valladolid in 1469, and their most famous protégé, Christopher Columbus, died there in 1506. Miguel de Cervantes, author of Don Quixote, lived and worked in Valladolid. Berruguete’s father, Pedro Berruguete (ca. 1450-1504), was also an artist, even more talented as a painter than his son, if a Madonna and Child of his on exhibit at the National Gallery is any indication.

Pedro had brought the Renaissance to Spain in a different fashion, introducing a Flemish “Northern Renaissance” style of painting that influenced many Spanish artists besides himself. After Pedro’s death, his son Alonso, then age 18, took off for Italy, where he lived in Florence and Rome for thirteen years and developed his talent for sculpture, befriending and assisting Michelangelo, Andrea del Sarto, and Filippino Lippi, among others. He also became one of the early promulgators of Mannerism, the 16th-century artistic style that emphasized extreme emotive expression—often via elongated figures in contorted positions–over classical harmony in composition.

When Berruguete returned to Spain and transformed his Italian training into an alabaster relief titled The Resurrection for the cathedral in Valencia, his work suddenly became in high demand. The Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, grandson of Ferdinand and Isabella and heir to the Spanish throne, made him court painter and sculptor in 1520. He turned from stone sculpture to wood, the traditional material of the medieval Spanish retablo, and his workshop in Valladolid, together with other patronage from Charles, made him a wealthy man. He continued to work in wood, marble, and bronze until his death at nearly age 80.

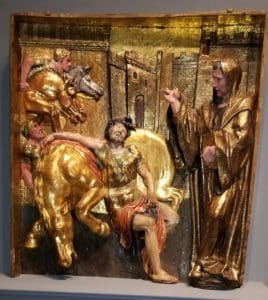

The retablo sculptures of Berruguete on display at the National Gallery, lavishly gold-painted and brilliant with color, are nearly always twisted figures caught in moments of emotional agony or religious ecstasy. A sculpture from the San Benito church depicting Abraham about to sacrifice Isaac displays a crouching, open-mouthed, nearly nude Isaac, his hands bound behind him and his body bowed over with terror (his figure resembles one of Michelangelo’s male nudes on the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling), while the gray-bearded Abraham gazes at the viewer in as much torment as his son. Two wooden prophets writhe in the divine power that inspires them. The most thrilling of Berruguete’s statues in this exhibition are his crucified Christ flanked by his mother, Mary, and the apostle John; their enormous figures once crowned the pinnacle of the San Benito retablo. Mary and John, both wrapped in swirling, voluminous gilded garments, grieve for the dead Christ, but more calmly, as seems fitting, than the emotion-charged figures from below. As for Berruguete’s Christ, his body, gray in death and looking as though it were carved from stone, seems utterly at rest, the bloody work of redemption complete.

For Americans—and others of the New World—Berruguete’s sculptures will resonate in an additional way. The Spanish colonizers of the Americas brought their retablo tradition with them to the churches they built there. Artistic styles changed over the centuries, but anyone who has visited the California missions or the cathedrals in, say Mexico City or Cusco, will find Berruguete’s lavishly decorated wooden edifices startlingly familiar. We have one of Spain’s greatest sculptors to thank in part for one of our own architectural traditions.

Charlotte Allen is a D.C. based arts reporter for Catholic Arts Today and the author of The Human Christ: The Search for the Historical Jesus.