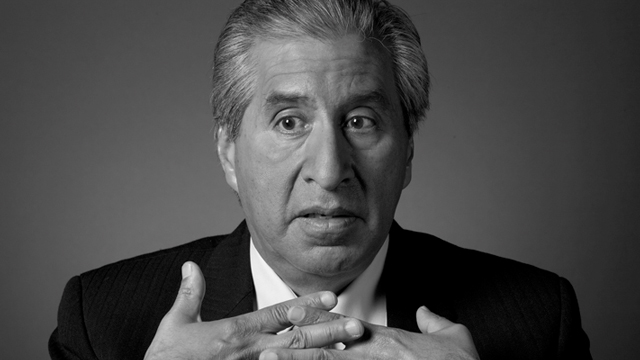

Richard Rodriguez was born in San Francisco in 1944 to Mexican immigrant parents who had only recently come to California. The family soon moved to Sacramento, the state capital, in California’s agricultural Central Valley. It was there that his parents enrolled young Richard, who could speak no more than fifty words of English, in Sacred Heart School run by the Sisters of Mercy. By fourth grade, he served as an altar boy in the last years of the Latin mass. At Sacred Heart, he learned what it was to be a Catholic in Protestant-majority America, where the forces of progressivism and individuality strove against the church’s preoccupation with sanctity, suffering, and the Four Last Things.

After graduating from Sacramento’s Christian Brothers High School, Rodriguez attended Stanford University, graduating in 1968. He went to graduate school at Columbia, and at the Warburg Institute (London). In 1976 he abandoned his doctoral studies in Renaissance English literature at the University of California-Berkeley to protest affirmative action. It was then he began a career as a journalist and literary essayist.

His first book, Hunger of Memory: The Education of Richard Rodriguez (1982), chronicled his journey from his Spanish-speaking family into the wider world of American possibility and loneliness. He wrote about the painful cost of separation from his family’s working-class culture. In that book, Rodriguez declared his opposition to bilingual education.

Drawing on his own experiences, Rodriguez distinguished between “public language” (which necessarily includes the language of school) and “private language,” the language of intimacy (which includes the language of home).

“It was my teachers’ role to tell me I was an American. The notion that you go to a public institution in order to separate yourself is absurd,” he said in an interview. Over the years, Rodriguez’s refusal to identify himself as Hispanic has led critics to brand him a brown Uncle Tom.

Hunger of Memory and his subsequent books have won Rodriguez critical acclaim and recognition as an elegant and perceptive stylist, one of America’s leading public intellectuals. His 1992 book, Days of Obligation: An Argument With My Mexican Father, reflections on Catholic California, was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize. Brown (2002) was nominated for a National Book Critics Circle Award in non- fiction. Darling, his 2013 collection of essays on religion after 9/11, was described by the New York Times as “the biography of many intersecting ideas: the relationship between gay rights and women’s rights; the relationship between unforgiving landscapes and enduring faith; between cities and their scribes; between a homosexual man and his church.”

Rodriguez is what we now term ‘openly gay’ (Rodriguez describes himself as a “morose homosexual”). He has lived in partnership with a man for forty years. But, “the church that taught me to understand love, the church that taught me well to believe love breathes—also tells me it is not love I feel.”

His description of Christianity, expressed in Darling, as a “desert religion” of emotional austerity fraught with hyper-masculine obsessions over power and blood and dogmatic points can strike many Christians as tendentious at the very least.

Nonetheless, Rodriguez says he remains “in love with” the Catholic Church, and he attends Mass faithfully in his San Francisco parish. His writings consistently display an understanding of Catholicism’s willingness to engage at the deepest level the inevitable human realities of humiliation, pain, weakness, and death—through the sufferings of Christ—in ways that other religions do not. He dedicates Darling to his first teachers, the Sisters of Mercy.

In a 2014 review of Darling for First Things magazine, the theologian Paul J. Griffiths recalled a speech Rodriguez had given on a theme that he had also explored in Darling: “[Y]ou can’t mock a crucifixion because it’s already a mockery”—and then Rodriguez imitated onstage the precise way in which being nailed, arms outstretched to a cross, strips a human being of every last shred of dignity.

On September 20, 2019, at the third annual Catholic Imagination Conference in Chicago, Rodriguez declared of us, his fellow American Catholics: “We’ve lost our imagination.” The Catholic Church, with its medieval theological edifices and deep engagement with suffering and tragedy that mark human existence, rests uneasily with the American goal of the pursuit of happiness. And yet in today’s America, he argues, Catholics have facilitated too easy an adjustment to the prevailing culture.

Rodriguez admits to a certain inscrutability; he is not easily pigeonholed as a “Catholic,” or “gay,” or “Latino” writer, though he admits to being all of these.

Charlotte Allen: I was fascinated by your speech, and I’ve read your writing over the years, since the 1980s. What I found most affecting was your description of the church, the Catholic church, as being a kind of lost culture in America. And you said in your speech, “We’ve lost our Catholic imagination.” And I wonder, what do you think of today’s Catholic Church in America? Where do the problems lie?

Richard Rodriguez. One of my favorite essays is a chapter in Days of Obligation called “Nothing Lasts a Hundred Years,” where I describe my Catholic imagination as interwoven strains from Ireland and Mexico. I identify myself as clearly influenced by my Mexican father’s tragic sense of life, and a liturgical tradition of the Dies Irae, and the Irish “vale of tears.”

Nowadays, the church wears vestments of joy and innocence at funerals. When I was a boy, I was struck by how un-American my boyhood was precisely because I was Catholic. America took no meaning from death; America took meaning from youth and rebirth, not from a mordant wisdom. In my Catholic youth, as an altar boy, I was often called out of class and sent to church, to assist at funerals. I watched grief, and knew that the people who were closest to the coffin were often the people not weeping; it was the people in the back pews who were weeping; they were the people who didn’t have to clean the body. The woman whose husband had Alzheimer’s for the last ten years of his life, she wasn’t weeping. That kind of thing. For a ten year old boy to ponder such things and then return to an arithmetic class was not a typical American experience of boyhood.

My Irish Catholicism was deeply sensual. (The stained glass windows of our church came from Dublin!) In the parti-colored light of a Saturday afternoon, I would assist at weddings. I would get fifty cents from the pastor to sweep the rice from the steps afterwards so people wouldn’t slip going to Sunday mass. Sweeping the grains of rice on a hot summer day in Sacramento, California, after the wedding party had noisily driven off was also a lesson in transience. The rice being a kind of relic of a joyous union, a union that I couldn’t imagine for myself, nonetheless, a ceremony at which I was attendant.

Charlotte Allen: Why do you think that you haven’t gained recognition as a Catholic writer?

Richard Rodriguez: The obvious answer is that I am sexually queer. Over the years, I have been interviewed by Catholic publications but for being Hispanic in America—not for being Catholic or homosexual. I get invitations to address Episcopal churches, for example, and Anglican conventions, even the national assembly of Episcopalian bishops.

Nothing like that would be possible in the Catholic church. I don’t get invited to speak about religion or about sexuality at Catholic universities or colleges. I’m not engaged by the Catholic church though it engages me.

And so, in some way, I guess I’ve never been taken seriously as a Catholic intellectual, as a Catholic writer, as a Catholic essayist. I’m normally shelved in bookstores as Hispanic. I’m not shelved as gay, either, because I am Catholic. And I’m not shelved as Catholic because I’m gay. So these categories seem to work against one another.

As I said in my speech to this conference, I owe my professional life as a writer to Jewish (albeit often secular) editors, television producers, critics. I call myself a Jewish Catholic writer. I think of Bill Goodman, who was the editor of my first book. He always encouraged me to write about my Catholicism, and he was interested in it.

As a Catholic reader, I’m always looking for Catholic writers, and there are many, though usually they don’t go by that appellation. More importantly, I have lots of friends who were priests or who are priests, and I’ve been sort of a counselor for troubled priests over the years. I’ve seen sexual addiction, alcoholism, profound loneliness. My interaction with clergy is not an intellectual Catholicism. I’m talking about the pain of shared lives. I knew quite early how lonely it is to be a priest.

Charlotte Allen: One of the things that did surprise me about your speech was the point that you made about the church not being what it was, and having died–essentially, that Catholicism is dead.

Richard Rodriguez: I think the most daring part of my speech was when I spoke about our fallen clergy—how we have turned our back on the sinner. With secular eyes we read stories about priests under arrest for sexual crimes. As Catholics, we used to have a more complicated relationship to sin. Even the decadent Renaissance Pope was a true pope, despite his sins, because of the grace of God. Priests and bishops who molest children are criminals and should be punished as criminals. But here is the astonishing thing: the sexual monsters were also our priests and bishops! The monster baptized many of us; the monster consecrated the host; the monster presided at the wedding of generations of Catholics; the monster buried our parents! What I am struck by is how we now won’t recognize our tie to these broken men.

Charlotte Allen: But some of the remedies that you suggested strike me as being more of the same. If we had women priests, for example, that would just be another kind of normalization, you might say, or accommodation with modernity. So, how do you reconcile those two things? You write of yourself as representing this lost tradition, but then you want there to be even more up-to-date-ness, so to speak, more feminism.

Richard Rodriguez: But the “up-to-date-ness” is the Catholicism I was raised within. I was raised by Irish women who were the first feminists of my life. They were my teachers! And when I call for women in the priesthood, I’m asking for the continuity of my Catholicism. Women were central to my Catholic formation. Just the simple fact, which the boy had learned quite early, that his teacher was a teacher not because it was her job or a profession, but because it was her vocation. Just that idea, that she’d come from Ireland to teach me in a room full of fifty students, and that it was a prayer for her. It was an act of faith. That teaching could have that spiritual dimension was something I learned through her.

Charlotte Allen: But why do you think that given the fact that you did have nuns as teachers, who saw that as their vocation, and that nuns can be teachers now, and are, and they fill all sorts of roles, why do they have to be priests? The kinds of power that women have are the kinds of power that women have had over you. That they are the nurses, they’re wives. Heterosexual men can’t live without women. They crave them.

They think their lives are nothing without them. So women exercise a huge amount of power in the heterosexual world that they seem to be unaware of, for some ideological reason.

Richard Rodriguez: To some degree, that’s true. But I think women now are raising families without men. Almost half the families in America are being raised by women in the absence of men. I think the weakness is clearly in the male. The male has grown so weak and unable to raise his own daughters and sons. That’s the shocking truth of the future we’re facing: Boys and girls don’t know what a strong man is.

They know what a strong woman is. Why give women more power? Well, I think segregating power between men and women limits our humanity.

Women have been so segregated in so many parts of the world that we don’t know what a woman even sounds like! What does a woman in a Taliban village in Afghanistan sound like? We Americans are in our infancy about sexual matters. We are promiscuous, but we don’t understand the dynamic of being a woman or a man. We are only coming to terms in America with the normalcy of homosexuality.

However, I’m enough of a sexist to believe that women are different from men, and that the world needs more women in power rather than fewer. I’d much rather be giving a speech to a classroom where there are women or girls. They are always more attentive; they have more questions, more imagination, more bravery to ask. And they all say the same thing: “How much your comments meant to me.” That generosity is, I think, is one way I associate with women. I’m sorry if that offends you, but I’d rather be interviewed for a job or a magazine article by— you—a woman than a man.

I support the right of women to be paid equally with any man for the same job. And I support the right of women to seek a place on any athletic team or corporate board. But it disappoints me to hear girls and women downplay sexual difference. I go to many schools where students refuse pronouns that are sexual and refer instead to themselves collectively as “they” or “we”? Many Hispanics these days are determined to challenge the Spanish language by no longer referring to “Latino” or “Latina.” They would neuter themselves, calling themselves “Latinx.”

Well, I am too old to be a Latinx. I am not an X! And I love the Spanish language. I love the whimsy of the Spanish language. But a woman would say, “Well, the sun in Spanish is el [sol], and the moon in Spanish is la, la luna.” And I’d say, “That’s nice. Because you can look at the moon at night and you won’t be blinded, but the sun is both nourishing but also blinding. It’s a wonderful whimsy of the Spanish language that the world has gender to it. That the lake has gender, that the forest has gender, that we could give nature that kind of personality.”

My closest friends, most of whom are dead now were people—I call them “darlings” in my book of that name—they were the people I gossiped with and laughed with; they were people who told me about their marital problems and raising children. We were not my sexual partners, but it seemed to me there was a liberation we achieved—the homosexual man and his heterosexual women friends. What’s more, I believe that the freedom I had “to come out of the closet” was possible at a time when women, the girls in my family certainly, wanted “to get out of the kitchen.”

I reject the puritanism now within the feminist movement—an inclination to remove sexuality from a consideration of our lives altogether. I want women cardinals in the Sistine Chapel precisely because they would be different from men. Nuns are different from priests, mothers from fathers, sisters from brothers.

Charlotte Allen: Last night, Paul Schrader [director, most recently of First Reformed] spoke. He mentioned you obliquely, not by name, talking about the Catholic imagination and it being associated with some of the things you described, Italian opera, for example. He said, “But that’s not the Catholic imagination. That’s Mediterranean. That’s Southern Europe. And Northern Europe is its own world.” You did posit this kind of opposition between Protestant America and Catholic Latin America. So, what he was saying essentially was that these were actually cultural differences, not religious differences. And I wonder if you have any response to that?

Richard Rodriguez: I think that’s wrong. I think my description of myself is as a Roman Catholic. But what that means is that I come out of a particular southern European cultural tradition, and that’s how Catholicism was expressed, through understandings of an Italianate sort. Though I’m also a Spanish Catholic, in the sense that the severity of Spanish Catholicism is very much part of me; that is the tradition that came into Mexico and that I inherited. Those national characteristics are, to me, very valuable. In the case of the Italianate, it did release certain kinds of strengths and weaknesses that we came to identify with all Catholicism. That’s Schrader’s point.

My only point is that I don’t think the novel is a particularly Catholic genre. But the kind of exclamation of the tenor on the opera stage feels to me more Catholic. And usually the tragic conclusion of the opera feels to me to be Catholic, as well as the scenery and the chorus. And that’s the way I live my life. I don’t live my life as one of Paul Schrader’s characters. He lives with a much more severe imagined landscape than I do. It’s not Roman at all.

I like it when in the Henry James novels a character is described as “Roman,” not because of their nationality, but because of their faith.

Charlotte Allen: When you said that the novel was a kind of Protestant invention deriving from Pilgrim’s Progress, what about Don Quixote? I always think of that as being one of the forerunners of the novel, and it has a Catholic origin.

Richard Rodriguez: Except I always thought of Quixote as coming out of a tradition of Dante, for example, the traveler. But there was also something unsatisfactory about his journey. Quixote was a sort of parody crusader. He was going nowhere. He was fighting the wind. Nothing would be accomplished, though chivalry was saved.

When I was a kid, there was a television cartoon series called “Crusader Rabbit.” Every afternoon there was another adventure. It was unending. It was like “I Love Lucy.” (I was shocked the other day to realize that “I Love Lucy” was on for only five or seven years. But decades later the comedy still plays, because Lucy is always getting into trouble with her schemes and making us laugh. That kind of serialization is very popular in Mexico, with the telenovelas. They just go on forever. And the adventures never end because they’re not leading to a point. There’s no novelistic conclusion. It’s just the pleasure of life, and the dejection of life, and the frustrations of life. And the journey. That’s all it is. The journey.

Charlotte Allen: Which is a very Catholic concept, isn’t it? The pilgrimage.

Richard Rodriguez And the other thing about the pilgrimage for Catholics is that: Bang! You can reverse it at the end.

Charlotte Allen: That’s right. You could do the worst stuff and…

Richard Rodriguez: Yes, and if the priest is there, you can confess it and…

Charlotte Allen: And that’s the end, right?

Richard Rodriguez: Everything that you have just read here is irrelevant. He’s going to heaven!

Charlotte Allen: It’s wonderful, isn’t it?

Richard Rodriguez: Yes.

Richard Rodriguez four books of essays can be purchased on Amazon here. His latest is Brown: The Last Discovery of America. He personally recommends Darling: A Spiritual Autobiography.

Charlotte Allen is a cultural/arts reporter for Catholic Arts Today.